Author Gerry Mc Donnell explores Irish Jewry in prose and poetry

In preparing for my recent visit to Ireland to learn about Jewish life there, I came across a March 2012 program produced by Dublin City University’s School of Communication and Inter Faith Center that featured Zalman Lent, rabbi of the Dublin Hebrew Congregation. Asked by one of his interviewers about places of Jewish significance in Ireland, Rabbi Lent highlighted Dublin’s synagogues and its Jewish museum, and then added that the city’s old Jewish cemetery in Ballybough was a noteworthy place to visit, too.

“I think there’s actually a book of poems … I think it’s called “Elegy” – “Mud Island Elegy” – that was written about the graves in the Ballybough cemetery. That’s quite interesting,” Rabbi Lent said.

Intrigued about this Irish poetry collection dealing with a Jewish cemetery, I searched online for the book and information about its author. Though out of print, I succeeded in procuring a copy of “Mud Island Elegy” (2001) once owned by the University College Dublin’s library. I also found that it was composed by Gerry Mc Donnell, a contemporary Irish poet and Dublin resident who subsequently wrote a number of other Jewish-related works, which were published by the Belfast-based Lapwing Publications.

Now a retired civil servant, the 68-year-old Mc Donnell’s Lapwing oeuvre includes “Lost and Found” (2003), an extended poem about a homeless Jewish man living in Dublin’s Phoenix Park and intimated to perhaps be one of the 36 righteous ones who, in rabbinic lore, ensure the continued existence of the world; “James Joyce: Jewish Influences in Ulysses” (2004), a slender volume of poems and short essays revolving around Joyce’s choice to make Leopold Bloom, the main character in his immense stream-of-consciousness novel, ethnically Jewish; and “I Heard an Irish Jew” (2015), a collection of poems and prose with Jewish content.

The final poem in that collection is “The Missing,” which references Irish mythology as part of a crushing critique of the way Irish bureaucracy prevented Jews from finding refuge outside Nazi-controlled Europe.

In the introduction to “Mud Island Elegy,” Mc Donnell describes how he grew up in the part of Dublin once known as Mud Island, containing the Fairview and Ballybough neighborhoods, but only became aware of its Jewish cemetery as an adult.

“On Fairview Strand, where at one time the sea lapped the shore, is a curious house with a more curious date over the door. As a child I wondered at this date which reads 5618. I wondered was it 1856 in reverse,” he recollects in the introduction. “The puzzle over that date, cut in stone, remained unsolved for me until recent times. I discovered that the house is the caretaker’s house for a Jewish cemetery which lies behind it.”

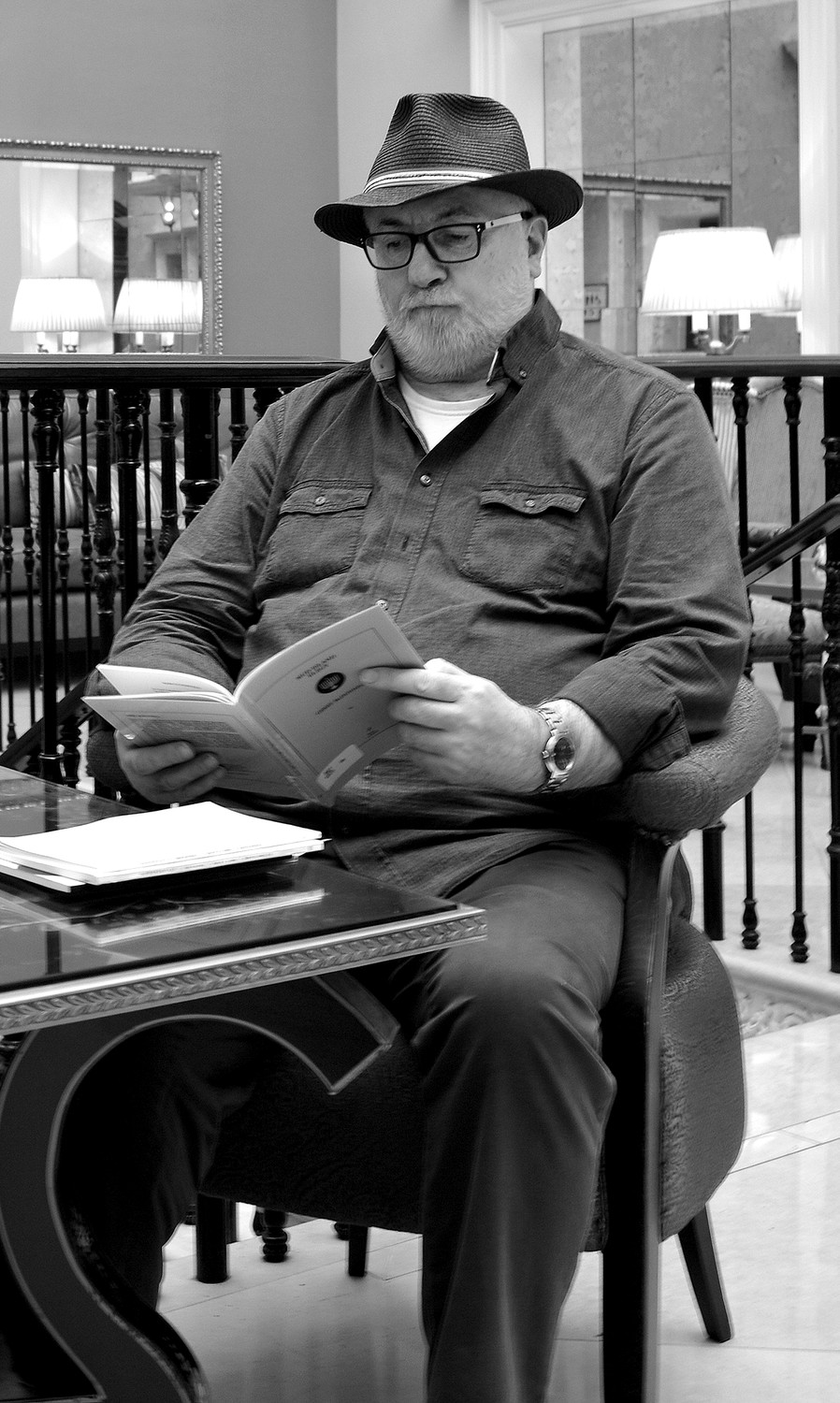

Having ordered, received and read several of his books, I hoped I might be able to see Mc Donnell when I arrived in Ireland, but my initial emails to him were all returned undelivered. Eventually, with the help of Lapwing’s Dennis Greig – who shares Mc Donnell’s curiosity about the Jewish people – I was able to inform Mc Donnell of my desire to connect in Dublin and discuss his work.

“I’ve received your correspondence from Lapwing Publications. I would like to meet you,” Mc Donnell informed me in an email. “I was thinking of the Westin Hotel on Westmoreland Street near Trinity College. I haven’t been in it recently but my memory of it is a spacious and quiet hotel. We should be able to find a suitable spot in which to talk.”

On the agreed-upon day, I made my way to the Westin Hotel from Trinity College’s Manuscript and Archives Research Library, to which I’d been granted access in order to gather information on Theodore Lewis, the Dublin-born and Trinity College-educated rabbi who moved to Rhode Island and then served as spiritual leader of Newport’s Touro Synagogue for 36 years.

After I located Mc Donnell, we found a quiet spot to sit, and ordered coffee and cookies. I’d asked him for a copy of one of his works that I wasn’t able to purchase, “Martin Incidentally: A Novella” (2013), which concludes with a short story related to Ireland’s failure to aid Jews trying to flee the Nazis during World War II. Mc Donnell presented me with the novella, and also gave me a 2016 Romanian translation of his “I Heard an Irish Jew.”

The Romanian book’s front cover displays a black and white photograph of one of Ireland’s most famous Jews, Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog, the Polish-born rabbi who lived in the Emerald Isle for 20 years, became chief rabbi of Ireland, was later appointed Ashkenazi chief rabbi of British Mandate Palestine, and then became the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel. The rabbi’s Belfast-born and Dublin-raised son, Chaim Herzog, was Israel’s sixth president; the rabbi’s grandson, Yitzhak “Bougie” Herzog, who was formerly chairman of Israel’s Labor party, still serves in the Knesset.

I asked Mc Donnell about his literary interest in Irish Jews.

“I don’t know why I was so interested in Jewry, except for that caretaker’s door we were fascinated by as kids,” he replied, referring to the Ballybough cemetery. “I bought a copy of Louis Hyman’s ‘Jews of Ireland: From Earliest Times to the Year 1910’ from the mother of a friend of mine. It had a registry of deaths, and my imagination just went wild with it.”

Joyce’s decision to place an ethnic Jew at the center of “Ulysses” – in part because he wanted a character who was a foreigner, representing the unknown and arousing the contempt of his Dublin neighbors – influenced Mc Donnell as well.

“ ‘Ulysses’ and Bloom also played a role. I felt an outsider myself as a writer,” Mc Donnell explained. “I was interested in the Other – in the Jews. In Dublin, they were outsiders. If you wanted a subject to write about, what better one?”

Mc Donnell has no regrets about the decades of labor he has so far poured into his craft.

“It certainly was time well spent. It was certainly better than working in the civil service. I never considered that my career. I considered writing my career,” he said, adding, “I still feel like I’m outside the inner circle of core Irish writers. I’m not good at publicizing my work.” Perhaps his persistent self-identification as an outsider helps explain why he continues to be so drawn to Jewish characters.

During our conversation, Mc Donnell disclosed a degree of uneasiness with being a non-Jewish writer of poems, stories and plays about Jews, as well as a recognition that he’s selected an obscure subject with a limited audience.

“I’ve always felt a bit of an interloper when I was writing about Jewish stuff, not being part of the community, and yet I can’t really get away from it,” he said. “With the Jewish material, there are not going to be people queuing up at bookshops, and yet it’s what I’ve chosen to do. Or maybe the subject chose me?”

SHAI AFSAI lives in Providence and is currently researching Irish Judaism. His full article on Gerry Mc Donnell, from which this one is drawn, will appear in the November issue of New English Review.